This is the picturesque road between the campground and the main stage at NewSong. It’s gorgeous during the day, but walking it in the pitch-black is a little sketchy.

I am secretly terrified of real dark like this here in Charles Town, WV, and I sing loudly to myself along the deserted way like I did when I was a child afraid of ghosts and had to go upstairs alone. I scan the ground for creatures. I know there is at least one group out there watching me, because I saw them in the daylight on another trek this way. There were chickens along the road, two loose from the pen and perched, as if to fool people about their abilities, on a low tree branch. Now, they ridicule me in the dark, the roosters wielding their morning-call power over me. How long can we make her wait out the night, they scheme. And you will have to wonder about what maniacal evil rooster laughter sounds like because it was too quiet for me to hear.

I mean, perched on the branch … who do they think they’re fooling?

I am ending my first day at the Mountain Stage NewSong Festival, which I’ve been dreaming of competing in since last December, when Tyler sent me a link to Brian Gundersdorf’s fourth-place-finish song while I was in Colorado . It was Brian’s song, “For One More,” that inspired me to start writing “In the Water” while I was there (see http://www.usatoday.com/life/graphics/new_song/flash.htm and click on the musician profiles if you want to hear Brian’s song). Brian amazed me by writing from a perspective completely outside of himself and his experience – what goes through the mind of a woman when a man she’s mostly just been fooling around with asks her to marry him – and I figured if he could do that and make it credible, well then I could write from the perspective of a drowned girl. So eight months later, here I am with my new song, inspired by NewSong, at NewSong.

I woke up at 7:30 a.m. , after crashing in Boonsboro for the night. Registration at NewSong started right at 9 a.m. and the first live rounds at 10 a.m. , and I didn’t want to be late. I was solo for this trip, and the silence allowed times and deadlines to tornado in my obsessive-compulsive head: 9 a.m. registration, 10 a.m. start, 4 minute performance time starting from your introduction. The last thing I wanted to do was be late, or to exceed my time. Then the obsessive-compulsive patter would quickly switch to an incessant chorus of: “But maybe if I’d only been five minutes earlier, or if I’d been ten seconds shorter. I wonder how many points I lost,” and that would make these a VERY long three days alone. I would never really know what I might have accomplished had I at least given myself the gift of starting everything right. Step one: be on time. I was in the registration line by 9:05

One of the performers had this as their hood ornament. A little more elegant perhaps than Daniel Lee’s skull and horns, but just as fierce. Grr.

Other than the members of We’re About 9, I worried that I would know no one else at the festival, but soon enough, the small, familiar world of folk music started to form around me. Isn’t that the host from the Tobacco Road open mic in New York City? And there’s Rod Deacey, who we shared a feature with at Frederick Coffee Company’s SNAFU. He owns a jewelry store and is always decked out as his best advertisement in an array of silver and gold. The multiple large rings he wears draw your eye to the beautiful long nails of his picking hand. He speaks with a British accent. I was grateful for his company in the registration line while I was getting my “am I doing this right?” nerves into check. Rod had been to NewSong last year, and we talked a little bit about that as similarly nervous and curious members of the registration line craned their necks to hear his answers and asked him questions of their own.

There’s something incredibly equalizing about moments and events like this. You could almost be a mind reader. Whether people say them or not, everyone in this line and walking these grounds is thinking and feeling the exact same things: Everyone is jittery, like middle school children talking about sex, finding surreptitious ways to confirm that they are “normal.” Everyone is afraid to be first, but can’t decide if the waiting is worse. Everyone starts making conjectures about their competitors, sizing people up based on the way they dress, the accessories they’ve chosen, their instruments on their backs and the stickers on their cases, their apparent nervousness or lack thereof, where they are from, their age. We use these tools to figure out what we think their music is like, how good their voice is. Are they kidding themselves here, or does everything about them say they are a major player? By Sunday I would know what I could not realize in those introductory moments: that I was in proximity to great success. I was standing in registration line next to a top-three finisher and would camp smack between two semi-finalists. I was hoping to make it through the first round.

I find out my slot is not until 2-4 p.m. , and it’s on the main stage, which I think is kind of cool. They assign me a round letter and a number, and the guy forgets to write my name on the sticker. So it reads only: C4. Hee hee. Explosive! Maybe it’s a good sign or maybe it means I spontaneously combust on stage. Who knows?

I took some of the free time to set up my tent. Let’s just say, right off, this is no KOA Kampground. Rob would HATE this. The only way I got him to camp the three times we did was with copious assurances that the bathrooms were nice and clean and there were showers. At the end of this field were two port-a-potties with an unlit lantern sitting between them to eventually mark their presence at night. The field had obviously been mowed a few days before, and browning clumps of grass were all over it, so it concealed the 3-inch brown spider with four black spots on it’s back that I almost kicked while setting up my tent (It was more interesting-looking than scary and all I could think is that if I were braver I could have caught Amy such pets!). One fire pit sat at the beginning of the field, which had thick woods on one side of it and a thin stand of trees on the other. I chose the latter side to set up, putting myself in the wide berth between two people who had already staked their claims. This way, I was guaranteed to have neighbors, and would be able to shake a little bit of the fear of being alone and sleeping outside in the complete country darkness.

Before I left for the festival, Tyler was teasing with me about my “bachelor pad” and meeting boys. Of course I had no intention of doing anything of the sort, so of course the musician camped next to me turned out to be a painfully beautiful man and a hell of a songwriter, Matt Cross.

He was wearing sunglasses, and as it is when you take in someone for the first time, they quickly became inexorably part of him. It was like he was always that way and didn’t have eyes to consider. I wouldn’t see them until later that day, when the clarity of their blue would surprise and disarm me more than I wanted to admit. He rounded the corner behind my tent with his electric guitar already slung around him, a 22 year-old from New York in a careless T-shirt – the picture of a rock star.

We found we had a lot in common, and I was glad to find someone I deemed a closer musical match for me than a lot of the other competitors at the festival. It made my being there among the hard-core folkies feel a little less ridiculous. He’d also competed the year before and made it to the semi-finals. He’d heard one of the riffs I was playing and thought it was sort of Tool-esque. Very cool.

We talked for a while before heading off to our separate destinations. Him: to “The Octagon” stage to compete in his round. Me: to the Main Stage area to survey the scene, eat lunch, calm my nerves, and watch the competition. Katie Graybeal from We’re About 9 turned out to be a judge for the round I was going to be watching, so we talked a little while before they started calling for a Matt Cross, the only competitor who hadn’t checked in for the round yet. I said something about him going to the opposite end of the grounds to compete at the other stage. This turned out to be an error, and I got the organizer to radio down to the other stage to send him the right way as soon as he checked in. He arrived at the Main Stage shortly after a little winded. I said he’d made good time and he said, “You could call it that.”

This is the roof of “The Octagon” barn, where the early-morning open mics were held Saturday and Sunday. It was absolutely huge and goreous at night.

He drew the last slot, so we got to sit and take in the other people together. I expressed my concerns about how the few people who were really different might have been too different to be accepted by the judges. He was of the other opinion, that they hear so much of the same kind of stuff that anything that stands out is better. He was unimpressed by most of the offerings, as was I.

My spectrum of mediocre has widened considerably after this festival. All living somewhere within that category are the bad voices/bad songs, bad voices/mediocre songs, good voices/bad songs, good voices/mediocre songs. There are the painfully nervous ones. Then there are the cliché songs that are still pretty good for the most part, but not stellar. Or people who are engaging performers, but the songs just don’t match up.

The bulk of the people I saw fell into this giant, atmospheric mediocre, but I also knew the judges would be choosing two from each round regardless of whether there was a stand-out choice or a lesser of not-so-evils. So I tried to get inside their heads and make my picks. I would later find out I was only right in a couple of instances. The judges change for each round, so it’s impossible that the patterns will be consistent or that you will know what is going to appeal best to which group.

When Matt finally got up to play, I was nervous. I wanted him to be as good as I surmised he must be, but everything about him visually said he might be more rock than this festival. He was a nice guy, the only one I saw to take up an electric guitar, and everything he’d told me said he was going to be something different. I didn’t want to be disappointed. He sang a song he’d written on the way home from last year’s competition, about a girl he knew who had an eating disorder. He handled the subject with care and cleverness and it was actually a really good song. Touching and even pretty in the face of its subject matter. He was sort of an alt-rock-folk, Jeff Buckley-esque sort of writer and player. My worries disappeared. And his performance bolstered thoughts that I could do this. When the semifinals names were listed hours later, his was among them.

Then it was time for my round. I told myself I did not want to go first and wound up drawing second to last, number 14. Brian Gundersdorf found me and mentioned that my round was stacked with some pretty major contenders, including the woman who had won the Kerrville Festival’s New Folk Competition only weeks ago. Still, my round offered up much the same mediocrity the last one had, with a few notable exceptions. I liked the Kerrville winner’s song. There was a guy from New York’s Tribe Hill collective who did a killer song and a killer performance, and would have been my vote to go on to the semi-finals, but he exceeded the time limit by more than a half-minute, which we all knew would be a nasty deduction. Another guy did one of the more clever anti-Bush songs of the million I heard that day. And a woman going by “Mother Judge” brought up a very different song and a very different voice, a deep alto that was a refreshing change in a round stacked with female singer-songwriters.

Finally, it was my turn to go on. I had my introduction down to one line (because I always talk way too much and say too little), and with the song included I was coming in at about 3:54 every single time.

The man onstage introduced me: Heather Lord.

And I paused for a minute, a little distraught; if I took the time to correct the man now, would they start the clock, robbing me of my precious buffer time? I opted to wait till the end, just to be sure. I looked out at the judges, sitting so far away that I really only saw them as a blond woman, a bald man, and another non-descript man. I started the song, accidentally adding a measure of guitar to the intro, which I worried might push me over. While I was singing the song, the world felt very slow and empty. There was no one sitting in the grass immediately before the stage – it was too hot in the open sun. Off in the distance, by the vendors tents, I looked out to see Katie and Brian watching. I reminded myself to look up, to look at the judges, to look out at Katie and Brian. But there was mostly just myself and the song, which for months of preparation, went by incredibly quickly. The end went by a little quicker because I sped it up just a bit to make sure I would still make time. I did, close enough anyway: 4:01 .

The man reintroduced me and this time I corrected him. He laughed and said, “Oh, Lloyd. Ha ha. Not the Lord,” at which point I lifted my arms in a Hallelujah pose and the place broke into laughter. People were coming up to me for the next three days, referring to me as “Not the Lord” and accompanying that with the gesture I made.

I watched the last round after me, and they started to announce the semi-finalists. When I heard Matt’s name, I was happy and encouraged. If he made it, maybe my song wasn’t too weird to make it, too.

But when they read the two names advancing from my round, mine was not among them. The anti-Bush anthem and a well-performed, non-descript folk song advanced. Not even the Kerrville winner made the cut, which made me feel a little better, though that must be such a strange feeling for her.

And normally I am the first one to get down on myself. To say that I am not good enough, to call myself a mediocre writer, singer, guitarist and performer. And I may very well still be all those things, but in this instance I firmly believe if I’d been judged by the previous round’s judges who advanced Matt, I might very well have been among the semi-finalists.

My small bit of obsession then turns to where I might have lost my points (because you don’t get to see what the judges said about you), and what better-suited song I might have done in that round. I have my theories. My biggest regret about it is that I just wanted to feel like I was taking something back with me. Not necessarily a trophy, but a little bit of affirmation from a credible source. Still, this contest, like so many, is incredibly subjective. And one of the hardest things about competing in something like it is realizing that there is not going to be any “truth” to be found there, not even if you win. Though maybe if I won, I wouldn’t give a damn about the truth. J

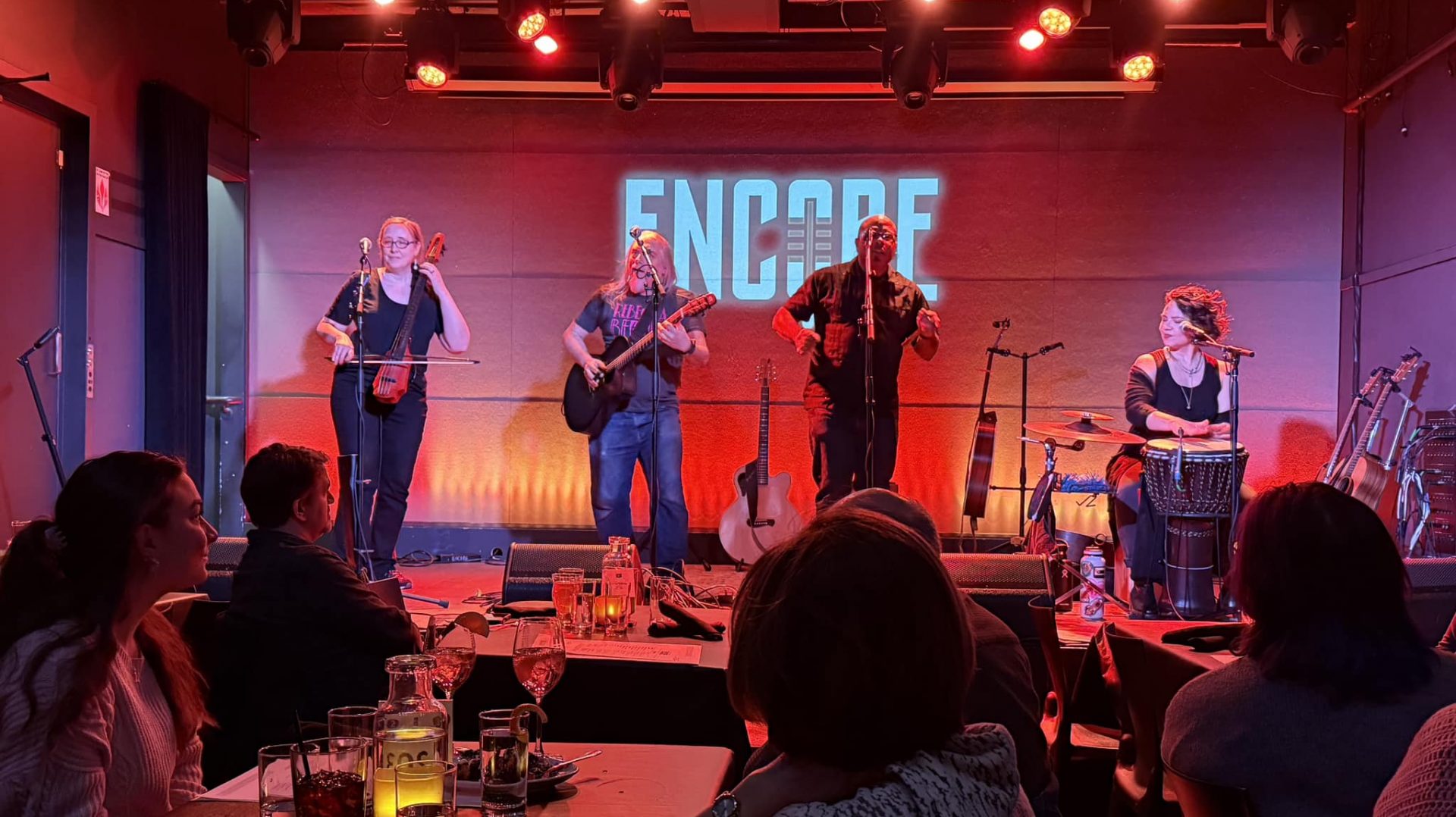

But the festival and the day did not end there. I went to see Brian, Katie, Devon Sproule and Jamal Millner do an in-the-round at one of the side stages. Jamal Millner was an amazing blues, hip-off offering amidst so much folk. I was glad for it and impressed that music like that was being invited to a singer-songwriter festival like this. While I was waiting for the show to start, three total strangers came up to me just to tell me how much they’d liked my song. People who praised me were immediately awarded with free sampler CDs, of course. J

I also bumped into one of my judges. I didn’t recognize her because of how far away she had been, but she recognized me. She told me how much she liked my song, and I thanked her, stifling the childish desire to say, “Apparently, not enough.”

I got back to the tent site right as it started to rain. By now the campground had become a small city, expanding not just along the treelines but into the middle of the grounds as well. Some people had built elaborate structures connecting the backs of their cars to their tents and making porches for themselves with rain tarps, which they were putting to good use as the rain worsened. Those who brought their families set up small enclaves, where the domed tents of various sizes looked like the set of Sealab. Others had single-man tents, which always have a habit of looking like escape pods or the coffins they launch into space in Star Trek. I lassoed an umbrella to the open trunk of the car and sat under it in the back, dangling my bare feet out into the rain.

But I was growing hungry and I didn’t have a dry place to cook, so I eventually went over to the Baltimore Songwriter’s Association awning at the campsite and asked if I could stay for a while. They agreed, marveling at the little gadget my father, Boy Scout camper extraordinaire, had sent me off with – a tiny propane-powered stove. I sat cooking my beef barley soup-from-a-can and drinking red wine while people sang and periodically pushed up the rain tarp with the necks of their guitars to keep the water from pooling and bringing it down. Refugees started coming from other parts of the campground, adding their songs to the mix. Peter, a Brit from Columbia , MD , played a beautiful song about Florence Nightingale. Three people from Ohio came over to play, two of them soon realizing they’d gone to high school together. Eventually I joined in and we let the thunder punctuate our lullabies.